Of Barbed Wire and Butterflies

Somewhere between an election, the stumbling roll-out of vaccines, and the exhausting pain flowing from the previous Administration, I feel like an eternity of noise and isolation is finally giving way to hope. There’s a light shining, however dimly, at the end of the pandemic tunnel.

Instead of listening to politicians harangue the opposition, I’m doing some stitching. Rather than watching Senator Hawley’s latest excursion into QAnon myths, I’ve been reading — I mean, not just email but books, those things that have covers and pages and authors. I’ve even been able to sit down long enough to watch a whole movie, beginning to end.

I think my rekindled interest in literature and film is related to something I’ve been pondering for some months: truth. This may seem like a leap, but under the hailstorm of lies we’ve endured, I began to wonder if there’s any truth that can be trusted, truth that’s reliable in a world of chaos and change. If such truth exists, I wasn’t sure where to find it, or how to express it.

During and beyond my college years I studied art. I learned from the great masters. I found comfort in galleries and the studio, in the ballet and the concert. In both seeing and hearing art, and increasingly in making art, I found truth — truth, the Britannica says, “impossible of attainment by any other means.” Art spoke a truth my soul longed to hear.

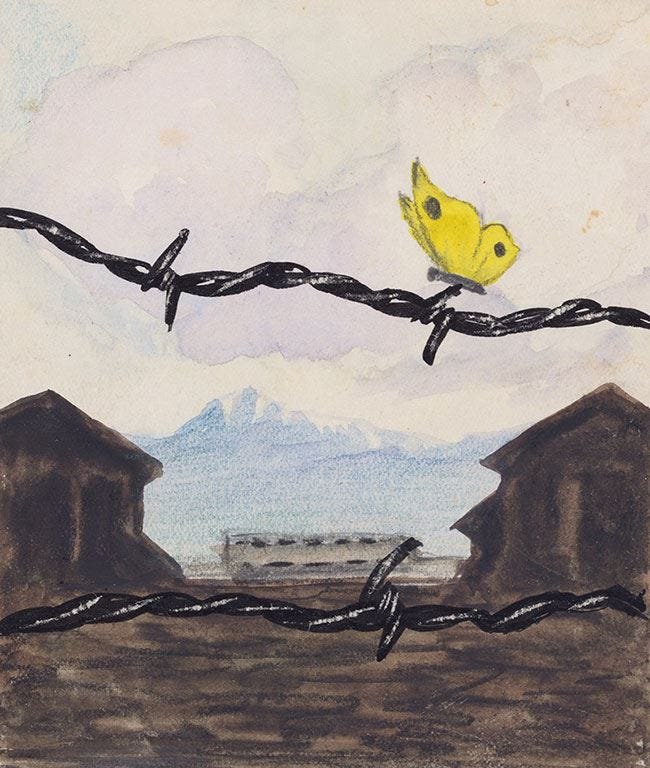

I remember seeing the little piece of art created by Kurt Conrad Löw and Karl Bodek, artists half-alive in one of Hitler’s camps. You’ve probably seen it: a brilliant yellow butterfly perched on barbed wire and set against distant mountains. I stood soaking in the sorrow and hope of their painting, knowing Löw had ultimately escaped into the mountains and Bodek had gone to his death in Auschwitz. The truth of that painting still moves me — the truth, as a later curator once wrote, that “one of them ended up with the role of the butterfly, the other did not.”

In 1995 I was mostly identified as an artist with AIDS. I’d given a speech that made some headlines, and I’d been invited by the U.S. Senate to have the first-in-history, one-woman art exhibit in the Senate Rotunda. Seventy-two hours before my exhibit opened, the invitation was pulled. One Senator had objected to one sculpture, a coffin-like piece around which I’d scrolled a line from one of my speeches: “Let us unite in life rather than in death.” The Senator was offended by the fact that AIDS was killing people. My art was telling the truth.

It’s been a few years since I was a practicing artist at work in my studio. I’m still amazed when people tell me my art has mattered in their lives, from a speech I gave or a quilt I stitched to a sculpture or a fabric or a photograph. When I wonder why something I made has mattered to them, I hope it’s that I told the truth and they knew it.

Last year, against the background of incessant lies, denials of the truth of science or the truth of events, I was deeply moved by Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste. I’ve not shaken it yet. Each time I think of the lessons she taught in her genius with words, I’m shaken again. Her art has given us an understanding of truth no mere history book could offer. It reminds me of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. It grips us as only art can do, with the truth.

Behind the events of Black Lives Matter and the death of George Floyd, is a long tradition of art in the music of “spirituals.” I’ve swayed with Black choirs as their voices soared and felt as though the music itself could heal my soul. Why? Because the music contains the most plaintive cries of those who were lashed to slavery — what the great Frederick Douglass described as “souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.” The music said what would, if spoken, cost a slave her life. It told the truth. Out of the horror of slavery emerged a cry for justice that sent John Lewis across the Edmund Pettus Bridge and lifted my spirit at the 16th Street Baptist Church where I was allowed to preach on the 30th anniversary of the church’s bombing. The truth lived in the soul-moving art of music.

I knew the truth last week when watching “The United States vs. Billie Holiday,” the truth that she was tortured for nothing more than being Billie. In absorbing “Nomadland,” I saw the truth of an economically abandoned community — those who didn’t die, left; even the zip code was removed — and one person’s relentless search for comfort, and meaning, and community. The extraordinary Frances McDormand practiced her art, and I could not let go of her truth.

When I visited women with AIDS in Africa, each day would end with songs and dances. We spoke different languages but knew a shared identity. We were all infected, all bonded by a virus we could not tame. In dance we found laughter, and in music we found love. The art of dance and of song lifted us to a shared truth.

Art offers a power and a clarity to truth that nothing else can. When Bryan Stevenson, the founder and director of the Equal Justice Initiative, created a museum to remember thousands of lynchings, he began with a sculpture. It tells the truth of slavery. When Heather McGhee wanted to explain the cost of racism to all of us, she didn’t work through charts. She wrote, persuasively, The Sum of Us. We rely on art when the truth is beyond reason.

And so it goes. Every year he was in office, the previous president tried to un-fund the federal cultural agencies that support the arts. I know why. It’s because of butterflies and barbed wire. Art, in all its glorious diversity, is the single most reliable antidote to deceit, the surest avenue to truth. A yellow butterfly and a strand of barbed wire tell us all we need to know.